Tumultuous childhood not enough to keep Church Farm’s Sibo Tuyishimire from smiling

EXTON >> Sibo Tuyishimire has every reason not to smile.

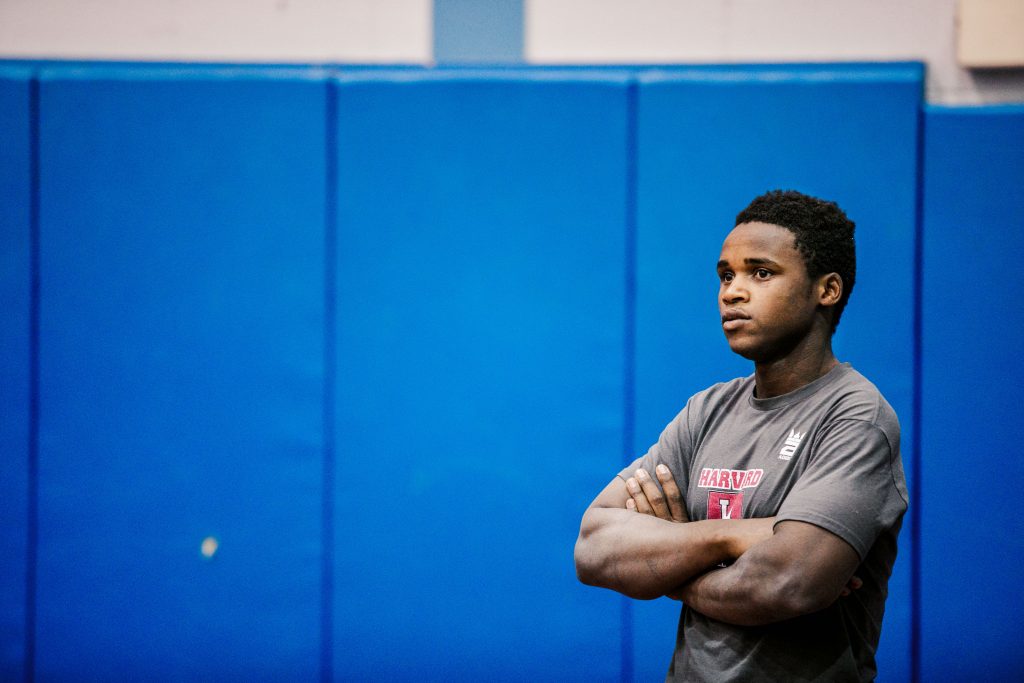

But, while hanging out before wrestling practice at Church Farm School, the sophomore can’t seem to find a reason not to.

Given the choice, Sibo, as he’s simply known around campus, grins ear to ear. As if he really has no choice.

There is an inner zeal that radiates from the Rwanda native.

His eyes beam with hope. His teeth flare from his mouth, exuding a rare happiness. A gap from an angled tooth, below his scarred upper lip, provides the only hint at an improbable existence.

But kids with stories like Sibo’s don’t usually smile like this.

Which begs the question: Did Sibo get to where he is today because of that innate joy, or is that joy a product of where he’s been?

“My wife (Padgett) said it, and it’s true, you can see his spirit,” Church Farm wrestling coach Art Smith said. “I don’t know if that’s because he had cancer or because he lost so many siblings. He could be one of those kids who says, ‘I don’t care about anything.’ If you looked at his story, you might understand that. He just keeps going.”

***

Whether it’s one of his first memories, or just a story his mother, Kantarama Eburaria, has described to him, it’s part of Sibo’s tale.

“My mom would carry me on her back and ask everyone she passed, ‘Do you know who can treat this boy?’” Sibo recalled. “People would tell her different words. ‘Oh, he’s poisoned.’ ‘He has a frog in his stomach.’ My mom, when she heard all these words, she would go crazy.”

As one of 13 children in a small Rwandan village near the Tanzanian border, Sibo’s family was not foreign to hardship.

The family business was farming, and while that got them by, day to day, the trials of a third-world country were evident. Sibo never knew his father, and 10 of his siblings died, either in the Rwandan genocide or due to health issues.

When Sibo’s nightly fevers persisted, and his distended stomach became raw, Kantarama was determined not to lose another child. Sibo doesn’t know his actual age, but he was likely around 3 years old when the sickness started.

From local doctor to local doctor, Sibo and his mother trekked, and herbal remedy after herbal remedy brought no results.

In 2007, after struggling to get treatment without the proper insurance, Sibo found help from a non-profit organization called Partners In Health, and Dr. Sara Stulac diagnosed Sibo with Hodgkins Lymphoma, and began chemotherapy.

“My mom said, ‘There is no way you can refuse to treat someone to save someone’s life because of health insurance,’” Sibo said. “‘It’s just a paper.’ She went and sold the house and brought the money and gave it to the nurses and doctor. Right away, the doctor wrote a transfer to another hospital.”

The chemo worked … for awhile, until the cancer returned. Sibo was sent to a hospital in Uganda for another round of treatment. The process was brutal. But for a young boy, who was robbed of a childhood and taken away from his family, Sibo’s spirit would not break.

“In my sickness, I was sick inside, but physically, I was strong,” said Sibo of his time in the hospital. “I would help my friends by pushing their (wheelchairs), taking them to the bathroom, making their beds, simple jobs like that. Many of them died, so I knew about death when I was young.”

In Uganda, Sibo’s condition did not improve, and his only chance of survival was to receive a bone marrow transplant — something not done in his region of Africa.

If he was going to live, Sibo needed to get to the United States.

***

Two years ago, in middle school, a wrestling coach at Hillsboro School in Massachusetts suggested Sibo try out for the team.

“Wrestling is all about not giving up,” Sibo said. “One on one. He told me I would be good at that. My first match I did good. I pinned the guy, but I didn’t know what I was doing. The ref was blowing his whistle but I kept wrestling. … I like how the sport encourages you to just keep working hard.”

Just getting on a mat was a success in itself.

In 2011, David and Renee Burns, who had fostered children in the past, agreed to take in Sibo in the suburbs of Boston.

There was hardly time for details, as Sibo’s condition grew dire. When he landed in Boston, doctors at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute discovered they’d have to treat his cancer again before the bone marrow transplant could even take place.

The chemo and radiation worked, and the procedure was successful. When Sibo finally got out of the hospital, he needed to stay isolated from the outside world for a year, with his immune system completely stripped.

The Burns family knew they were inheriting more questions than answers, but through it all, Sibo’s demeanor was undeniable.

“Even though he just came and was sick and didn’t really understand much English, we could tell he was a very engaging, caring kid,” David Burns said. “As he stayed with us and learned more English and got more comfortable and started to feel better, you could see he really was special. He was poked and prodded and almost died numerous times. If anyone deserved to be negative about something, it was him, but he carries none of that with him. He just walks in grace.”

In wrestling terms, death had Sibo on his back, but he rolled through.

“I’m so grateful I’m alive, now,” he said. “I’m very focused. Starting from 2011, I started to look at what I wanted to be and what I want.”

The documentation Sibo was given, to be allowed to fly from Africa to Boston, said he was 21 years old. Doctors in the US settled on 16 for his estimated age, and after hearings with District 1 and the state, the PIAA granted him three years of eligibility, in the fall.

Now, he’s a starter at 126 pounds for Church Farm, with a record of 12-14 (as of February 13).

“The thing that really stands out to me is his unbridled joy, every day,” Church Farm athletic director Greg Thompson said. “I think almost all of our kids, with the fact that they’re teenage boys, appreciate the opportunity that they have here, but for him, he just loves it. He soaks it up, every minute, every day. In soccer season, he couldn’t play, but every game he wanted to run lines. So, he’d come down there and run lines, with a passion, all game just wanting to be a part of something. He’d be running up and down the sidelines yelling ‘Let’s go brothers, let’s go Griffins.’”

Smith can’t help but laugh about Sibo’s penchant for getting headlocked. That’ll come with time and practice. After what Sibo’s been through, getting pinned is but a blip.

“He smiles all the time,” Church Farm teammate Ziting Liu said. “I’ve never seen that before. He’s always smiling, all the time, when we’re having problems and stuff like that. He’s very optimistic.”

***

Sibo recalls one of the first times he got in trouble.

His older brother was sent to the swamp for some water, and Sibo tailed him. Instead of fetching water, the older boys got sidetracked throwing stones at monkeys in the brush.

“I was standing behind, watching what they were doing,” Sibo said. “The monkeys started getting angry, jumping all over the trees, towards my brother. My brother and the rest got scared and turned around and ran. In running, they passed by me, going back home, and I was behind. I followed them, running. The monkey got a stick, starting beating me, running back to the tree, beating me, running back to the tree.”

If sympathy was what he hoped for when he escaped, Sibo found the opposite.

“I went home, crying,” he said. “My mom saw me, ‘Why are you crying?’ I said, ‘Oh, a monkey beat me. I followed my brother.’ My mother was angry. ‘I told you not to leave.’ So she got a stick and beat me again.”

Sibo laughs about it now. It’s one of the fond memories he has of home. This summer, Sibo hopes to return to Rwanda for a couple months.

He hasn’t been back in three years. After recovering from his transplant, Sibo flew back, with Renee, and he got his first taste of schooling.

Having never been formally educated, Sibo was placed in a grade suitable for his age, but not for his baseline knowledge.

Sibo caught up, learning his ABCs, while classmates read, and eventually placed in the top percentiles in Rwanda’s national test.

It was then, the Burns family brought him back to the states, initially at Hillside (which only went up to ninth grade) and now to Church Farm.

“It’s a blessing,” Sibo said. “If (Renee) didn’t come back with me, I don’t know where I would be. Looking back to my family in Rwanda, a lot of my family, they’re out there everywhere, working for food. All they do is just work for food. So I would probably be like them.

“Me being here, I’m grateful for that,” Sibo said. “This is my chance to make something. Maybe help my family and anyone else who needs my help. It’s a great opportunity I have and I really understand it.”

***

While trying to recover a pet guinea pig, as a little boy in Rwanda, Sibo got a little too close to his older brother, who was digging out a hole in pursuit of the run-away rodent.

On the backswing, the hoe caught Sibo’s mouth, taking a chunk out of his lip.

The lasting scar and gap in his teeth are the perfect complements for a brilliant smile — a reminder that a horrid past does not negate a promising future.

“It’s a very big opportunity I have,” Sibo said. “Seeing me here, in the USA, having an education, many people in my village don’t have this chance. My goal, I want to very carefully take this chance and do something that will help others. I want to be a doctor when I finish and go back to Rwanda and help people the way I was helped. So many people did a lot of things for me, for free. This is, I don’t know how I can describe it, so I really want to give back, too. That would make my heart feel happy.”

The chances of a young boy with cancer in a remote village on the continent of Africa, finding a path to healing, to an education, to hope, are one in a million.

Sibo seems to realize it. As much as he’s been blessed, his journey has paid forward the blessings, tenfold.

“It’s more than I think we anticipated, but every day, every month, every year, it’s just another chapter, and it brings a smile to our face,” David Burns said. “I’m really intrigued about how the rest of the story plays out. I feel like we’re in the middle of a really intense story, and I’m excited to see how it unfolds and what the future holds for him.”

The legendary Olympic wrestler and former Iowa head coach, Dan Gable, famously said: “Once you wrestle, everything else in life is easy.”

Sibo may see that a little differently. From where he’s come from, and the odds he’s overcome, wrestling is just another thing to smile about.

“He could not win another match the rest of his career and I’d still be impressed with him,” Smith said. “But that’s not going to happen, because he wrestles to win.”