In first season at Malvern Prep, Susan Barr focused on being present, not a pioneer

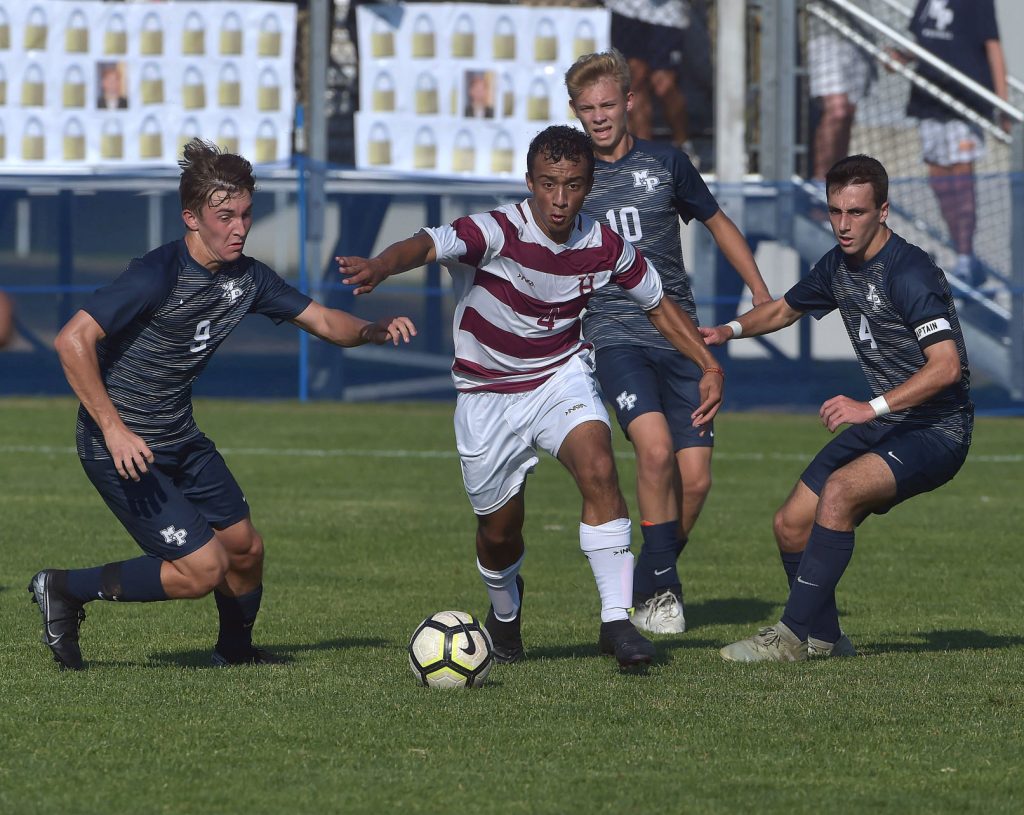

MALVERN — Susan Barr calls her team together for a postgame huddle. It’s early October, and Malvern Prep had just lost a 1-0 decision to Haverford School, a tight game in keeping with the Inter-Ac’s usual parity and density of skilled players.

Her short blonde hair under a hat, Barr directs her intense coach’s stare at the huddle as she runs through talking points, illustrating things that went well, highlighting areas for improvement, lauding the team’s fight.

There’s little in the postgame confab, short of uniform color, to differentiate it from the one the Fords conduct at the other end of the field or from any of the other high school squad in the area. To Barr, it’s just a coach convening her players.

From the outside, though, something is notably different: Barr is one of a select number of women coaching boys/men’s soccer scholastically in the United States. Her qualifications as a coach and knowledge of the game make her vastly qualified. But the prevailing demographics suggest that for many other qualified women in her profession, such facts don’t always win out.

Barr insists that being hired to coach a boys team — even at a centuries-old, all-boys school like Malvern Prep — was a “non-event” back in the summer, when she became the first female varsity coach in the school’s history. Gender wasn’t a consideration: She saw a soccer opportunity, with all its complexities, and like countless others in her long career, she jumped at it. And she’s reticent to have her role serve as anything more than a coach seeking the next challenge in soccer.

“I think for the longest time, the last thing I wanted to be was any kind of representative for equality within the sport,” Barr said recently. “I was just focused on my own development to be honest. I think now that I’ve been doing this for a long time, that I’m older, I realize that I probably could break down some of those barriers that are there just by being present.

“It’s not something I want to talk about, but just by being here and being responsible and being good at my job, hopefully that lends itself to that. I love a challenge, so where else do you want to do this but an all-boys school where athletics is a big part of who they are?”

Barr’s history in soccer speaks for itself. The Ithaca, N.Y., native was a two-time All-Ivy League performer at Cornell. She and her husband settled in the Midwest, where she coached girls at Columbus North High in Indiana. They moved to the Philadelphia area for work, and Barr stepped back from coaching to raise three sons. But eventually she caught the bug again, starting youth programs at YSC Sports in the mid-2000s and growing what would become Union Juniors.

“Sue always loved the game and went out and did all the extra work and got licensed, and now is become one of the top-level female coaches in the area,” said Charlie Dodds, the varsity boys coach at West Chester East as well as the president of YSC Sports. “She put her mind to it and spent a lot of time and effort, and you go to any coaching clinic and any coaching seminars, and Sue’s always there with a pen and paper trying to learn. … Sue’s always been the person that’s always having conversations about how to become better.”

One thing led to another in Barr’s avid quest for self-improvement. She earned an A License, the second-highest below the pro coaching license, from U.S. Soccer in 2015. She’s completed instruction from the United Soccer Coaches and its predecessors, gotten licensed by U.S. Youth Soccer and last year attained a Grassroots Instructors license from USSF, allowing her to instruct coaches. She’s also worked with Eastern Pennsylvania Youth Soccer’s ODP program and is a staff coach at Penn Fusion, currently working with girls.

It’s a stunning resume for a high school coach. Mike Barr (no relation), EPYSA’s technical director, estimates that the number of high school coaches, for boys or girls, in Southeastern PA with an A license is in single digits. Susan is the only one in Pennsylvania with a Grassroots Instructors badge.

“She’s really unique in a sense that when you have male coaches coming in, they’re not one to ask for help,” Mike Barr said. “But when Sue had issues or was asking about a session plan she was doing with her A license, when she needed help, she was willing to ask. And to me, that’s the sign of a great coach. She just wants to learn. … Sue just wants to be the best.”

When Malvern found itself needing a coach in the spring, Barr stepped in to help players, including youngest son Kieran, keep fit in the offseason. She’s familiar with the school’s mission as a parent dating to when her eldest son played there.

It made for a perfect marriage on and off the field.

“She’s been a fantastic example for the kids,” said Malvern athletic director Jim Stewart, who made Barr his first coaching hire. “Her coaching ability is extraordinary. What she’s been able to put together with these guys, even though their record is still under .500, what she’s been able to put together and for the most part keep their heads in it, has been really amazing to watch.”

Despite the ease with which Malvern and Barr handled it, hirings like hers are rare enough to spur these types of articles. The smoothness begs the question of why such moves are so rare. In contact sports like basketball and soccer where male and female versions are essentially identical — Barr likens it to a “dotted line” in how the games’ tactics have co-evolved — the friction of pivoting from coaching one gender or another should be slight … as it generally is when men trade make the switch. Opportunities to women to make the analogous jump, however, trail far behind.

High school coaching data is largely anecdotal and unreliable. But NCAA data offers a window into the rarity of women coaching men’s soccer. Only one men’s soccer team in the NCAA, out of 830, had a woman as head coach in 2018 (New York University’s Kim Wyant). A paltry 22 of 1,802 assistant jobs in men’s soccer belonged to women. Even in women’s soccer, women constitute a minority of head coaches (35.3 percent) and a slight majority of assistant coaches (51.1). The head-coach percentage in Division I is even lower at 28.4 percent. Estimates by United Soccer Coaches, whose nationwide membership exceeds 30,000, places the female proportion at about 15 percent.

The reasons are variable — some women prefer to devote themselves to the women’s game; others see the lack of pay as untenable; others, as Barr did, prioritize family responsibilities. Not every woman aspires to coach men. But the disproportionality indicates that a lot is impeding those who do.

“I don’t think the barrier is the coach, and I don’t think the barrier is the player,” said Nancy Feldman, the longtime women’s soccer at Boston University, who Barr counts as a mentor. “I think the barrier is a societal stigma that that doesn’t seem normal. The more it’s done and the more Susan is a pioneer … the more it’s going to happen because it’s not going to be something that seems so unusual.”

The Friars have had a tough go of it this year, with a young team that has won just four games in a league stocked with talent. But Stewart raves about the job that Barr has done.

Barr has managed a number of challenges, and a gender divide is low on that list. (The biggest issue? Sending an assistant to fetch guys from the locker room.) For one, moving from club to high school is a different animal, given the holistic scope for four long months, a nearly full-time job to coach varsity and managed three other levels in the program. While this wasn’t the intended destination of her coaching journey per se, Barr’s long lens of experience has helped — her poise as a well-respected coaching fixture, her connections for recruiting and the wisdom of a mother who’s cared for students at his level.

All those far outweigh what locker room she can go in. And they mean she can focus on why she took the job: To teach through soccer.

“We’ve never talked about” the gender question with her players, Barr said. “It was pretty much, ‘let’s go, it’s time to get down to business, we have a lot of work to do. … I think they appreciate having someone that’s qualified and that cares about them.”